Desertion and punishment statistics emanating from World War One records also reflect inherent and divergent interpretations of military laws and codes. The Army Act of 1881, when flogging was abolished, the 1912 edition of the King’s Regulations and the 1914 Manual of Military Law formed the basis of British military law. However, it could never be envisaged that hitherto unknown prolonged static warfare of industrial proportions lay in the near future, which would leave military codes largely wanting.

Presiding courts martial officers were often subjective in their understanding of what constituted desertion, and in the chambers of Westminster, the morality of shooting your own soldiers for desertion and cowardice polarised the political spectrum.

In April 1930, while hotly debating the issue of the death sentence as a punishment for desertion in the House of Commons, Secretary of State for War and Labour politician, Thomas Shaw, contended that the line between what constitutes cowardice and desertion was, at best, tenuous. Hansard, the official record of parliamentary proceedings, shows Shaw arguing that the two offences were “manifestations in different form of the same failure of nerve power or will power”, adding “if you allow the death penalty for desertion to remain you allow a penalty to remain which was responsible for no less than 92 per cent of the executions in the last War”.

The Army Council, however, countered the proposed abolishment of the death sentence—of which, ironically, Shaw was a member—by insisting ‘. . . dreadful and horrible as it is, it is a sanction which is essential to the discipline of the British Army’. Pro-capital punishment members of the House, however, believed there was a plausible ‘essential’ difference between the two crimes. Desertion took place “not in the heat, turmoil, and horror of the moment of battle, but probably somewhere behind the lines where the man at the moment of desertion is under peace conditions and safety, and he deserts to avoid the danger which he knows lies before him if he carries out the dangerous duty which he has been ordered to do”.

The inference, shared by the Secretary of State for War, but for different reasons, was that the overwhelming majority of desertion convictions were in fact cases of mental distress, commonly referred to as ‘cowardice’.

Hansard records Shaw as saying, “There is no romance in mud, vermin, and shell and shot, where men are destroyed without a possible chance of seeing the enemy they are fighting. There is no romance in that; it is simply brutality, dirt, disease and death. Where a man is engaged regularly in the Army you may be right in shooting him for cowardice, but you have not the same right in the case of civilian volunteers. You have no right to take a man from the factory or the farm and put him into khaki and a tin hat, and then shoot him if he shows cowardice”.

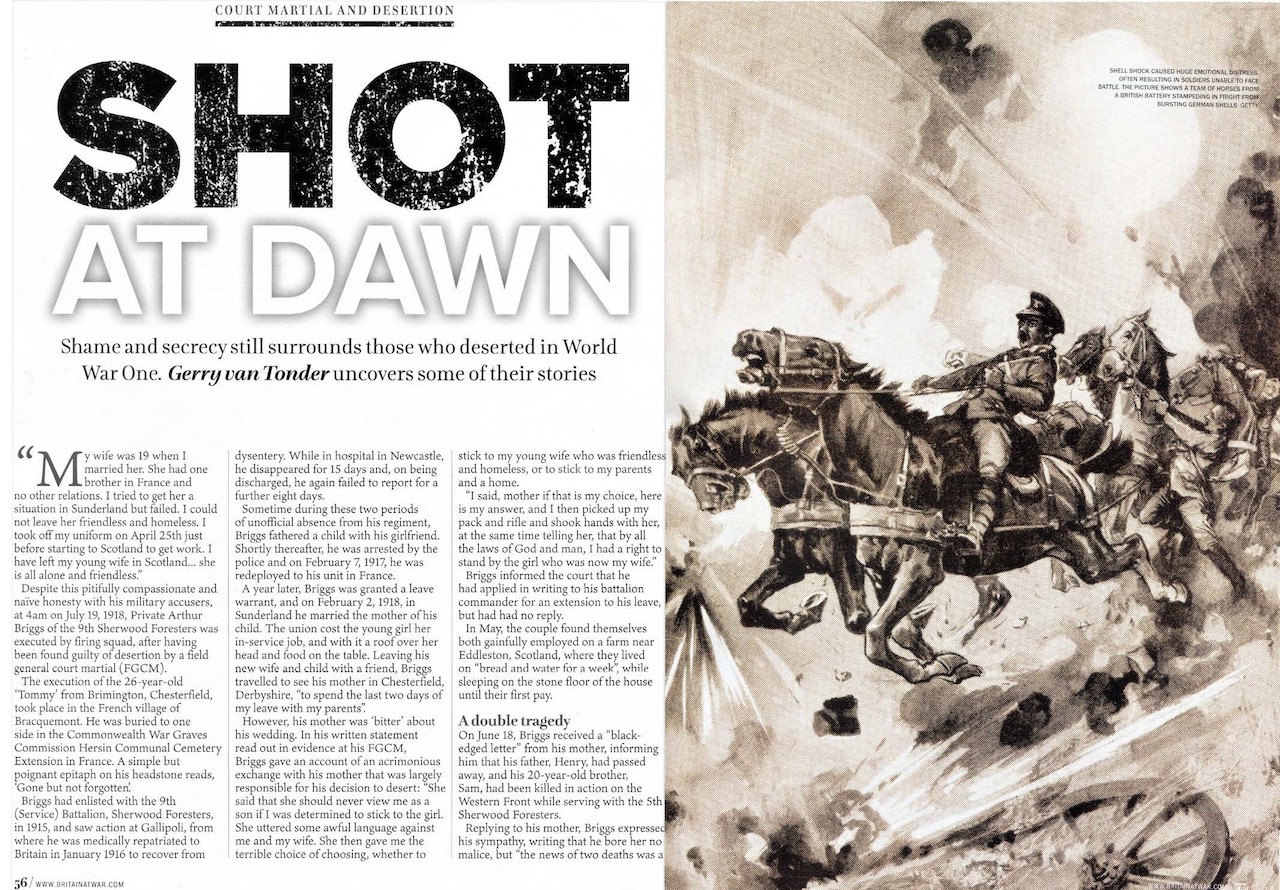

First coined during the conflict by British psychologist Charles Myers, the term ‘shell shock’ was used to describe what would become known as post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD. However, it would take decades of medical advances to fully understand the psychological and physiological trauma experienced by so many soldiers during the war—the so-called invisible wounds.

Victims would present symptoms such as uncontrollable anxiety, facial tics, loss of sight, stomach cramps, hallucinations, and the inability to eat, sleep, walk or talk. Treatment varied considerably, depending on a medical practitioner’s diagnosis. In many cases, soldiers with shell shock were belittled as they were not ‘man’ enough to deal with the war. The imperative was to return the soldier to the frontline as quickly as possible. Others understood the cause to be as a result of a physical nerve injury, brought on by a soldier enduring prolonged heavy enemy bombardment.

Using full field court martial documentation for Private Arthur Briggs of the 9th Sherwood Foresters, I follow his trial, circumstances and execution by firing squad in France in July 1918. The descendants of Arthur Briggs—and those of all the other 305 men who suffered the same horrific end of life—had to wait 88 years for the powers that be to recognise that these executions were wrong.

Janet Booth, granddaughter of Private Harry Farr, who was shot for cowardice in 1916, campaigned and lobbied tirelessly from 1992 until 2006, when Farr’s family eventually took the British Ministry of Defence to Court. They won their case, and under Section 359, ‘Pardons for servicemen executed for disciplinary offences: recognition as victims of First World War’, of the newly promulgated Armed Forces Act 2006, every one of these soldiers shot during the First World War was granted a pardon. The Act does, however, make it clear that the pardon only applies to the actual execution, and ‘. . . does not lift the convictions or sentences of the servicemen affected’.

Only a few years earlier, on July 24, 1998, the Minister for the Armed Forces, Dr John Reid, told the Commons, “There are deeply held feelings about the executions. Eighty years after those terrible events, we have tried to deal with a sensitive issue as fairly as possible for all those involved. In remembrance of those who died in the war, the poppy fields of Flanders became a symbol for the shattered innocence and the shattered lives of a lost generation. May those who were executed, with the many, many others who were victims of war, finally rest in peace.”

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.