“Two minutes; one minute; thirty seconds; men gasped—perhaps a brief prayer. A mighty roar shook Douai Tunnel and all that trench world, and the stupendous, stunning barrage of 9 April crashed down before the Highland line. In a flicker of time the dawn was raving. A frantic shower of coloured lights sprayed up through the fog from the German line.”

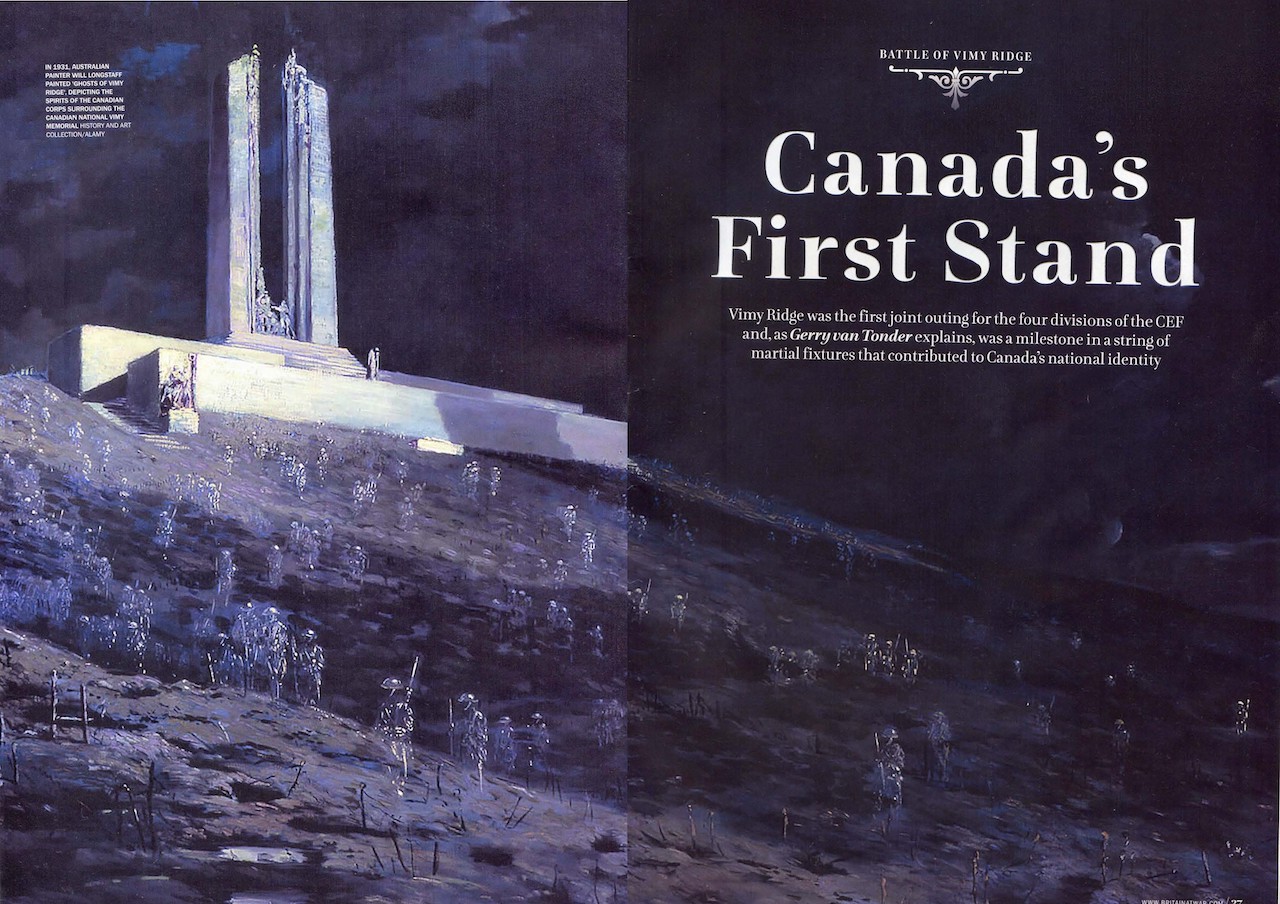

Kim Beattie, chronicler of the 15th Battalion, 48th Highlanders (Toronto), 1st Canadian Division, dramatically portrays the seminal moment in this British dominion’s history which, in the words of author John Pierce, “came to symbolize Canada’s coming of age as a nation”. The battle was the first occasion when the four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF)—titled the Canadian Corps—fought together, and made a symbol of Canadian national achievement and sacrifice.

At the outbreak of the war, Canada was still 17 years away from being granted legislative independence by Britain, promulgated by the Statute of Westminster 1931. Therefore when Britain declared war, Canada found herself at war, even though ‘she had not been consulted; she had herself made no declaration of war’. But there was never any doubt that Canada would give her all, as reassuringly expressed by Governor General Field-Marshal H.R.H. the Duke of Connaught, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, “that if unhappily war should ensue, the Canadian people will be united in a common resolve to put forth every effort and to make every sacrifice necessary to ensure the integrity and maintain the honour of our Empire.”

However, the dominion faced a Herculean task as an ‘unmilitary nation’ with extremely limited resources and facilities to commit a fully trained and equipped expeditionary force for active service overseas. As of April 1914, the total authorized establishment of the permanent force was 3,110 all ranks. Supplementary to this there existed a ‘Non-Permanent Active Militia’ which, by 1913 stood at around 55,000.

In the Spring of 1917, the German Army High Command accepted the inevitability of a major French and British offensive, and to shorten the line, took the tactical decision to fall back from the Arras–Roye Soissons bulge onto the Siegfried Stellung—the Hindenburg Line. The total destruction of the zone they were vacating would be integral to the withdrawal. Early in March 1917, Lt Gen Sir Julian Byng, commander of the four-division Canadian Corps planned for a four-phase attack, each represented by a coloured line on the map. At an average distance of 750 yards from the Canadians’ front trenches, the Black Line, together with the enemy forward defences, would be the first objective. The Red Line ran north along the Zwischen Stellung from the divisional boundary with the 51st (Highland) Division to a point just south of Petit Vimy. From here, it swung northwest along the right flank of Hill 145 and Vimy Ridge, to the 24th (British) Division boundary.

This represented the final objective of the 3rd and 4th divisions attacking on Byng’s left flank. Onhis right, however, the 1st and 2nd divisions would still face two more objectives: the Blue and Brown lines. The first required capturing the village of Thélus, Hill 135, and the Bois de Bonval and Count’s woods, thereby securing a commanding position overlooking the village of Vimy. The second objective covered the German Second Line, running through Farbus Wood, the Bois de la Ville and part of the Bois de Bonval.

By midnight, Easter Sunday, April 8, 1917, along the whole Canadian Corps sector, thousands of troops of the four divisions, weighed down with combat equipment, moved forward to take up their respective jump-off positions in the forward trenches. Sleep had been impossible in the all-consuming pre-battle tension.

Zero hour and the Allied guns commenced a carefully stage-managed rolling barrage in front of the poised Canadians. Hundreds of Canadian Vickers and Lewis machine guns swept a zone 400 yards ahead, as the corps troops went over the top on the heels of the artillery barrage. They surged ahead against a thin rain with intermittent snowfall, focussing on the first objective, the Black Line the Germans called Zwölfer Weg.

Only threequarters of an hour after zero, the 1st and 2nd divisions had achieved the Black Line objective. The 3rd Division encountered only light resistance but the 4th Division faced the greatest difficulties—it would take them several hours to take their first objective. By 11 April, running for a length of 7,000 yards, and with a depth of 4,000 yards, the whole of the main part of Vimy Ridge was now securely held by the Canadian Corps. In the two days of fighting, the Canadians has suffered 2,967 killed and 4,740 wounded. At the end of war, the 1st and 2nd (Canadian) divisions formed part of the Allied occupation of force of Germany. The Canadian Corps was demobbed in 1919.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.