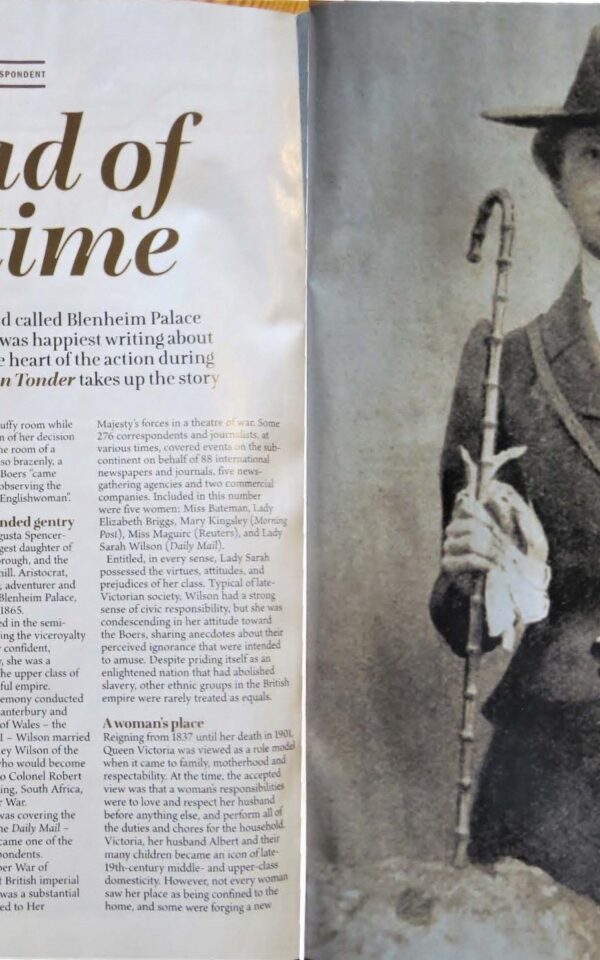

Born on 4 July 1865 at Blenheim Palace, Lady Sarah Isabella Augusta Spencer-Churchill was the youngest daughter of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, and the aunt of Winston Churchill. Aristocrat, war correspondent, spy, adventurer and nurse, she was one of the first woman war correspondents in 1899, covering the Siege of Mafeking during the Second Boer War for the Daily Mail.

In 1891, in a lavish ceremony conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury and attended by the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, Lady Sarah married Captain Gordon Chesney Wilson of the Royal Horse Guards, who became aide-de-camp (ADC) to Colonel Robert Baden-Powell at Mafeking.

Typical of her class and late-Victorian society, Lady Sarah had a strong sense of civic responsibility, but she was condescending in her attitude toward the Boers, sharing anecdotes about their perceived ignorance that were intended to amuse. Society was, in effect, governed by men of the wealthy upper classes with political affiliation, men who advocated that women should be seen as sacrosanct, to be submissive ‘helpmeets’ in charge of motherhood and morality, but certainly not to take part in an active life outside of the Home”.

However, it also came at a time when ‘corset-bound’ British women started to speak out about gender equality and the personal right to freedom from domesticity and access to explore opportunities beyond institutionalised sexualism. But in the Victorian society where ‘duty, character and chaste behaviour were of paramount importance’, the concept of the independent ‘New Woman’, complete with self-determination when it came to education, work, travel and feminist activism, was anathema to all but a tiny minority.

Her first visit to southern Africa, in December 1895, coincided with Dr Leander Starr Jameson’s ill-conceived and disastrous filibuster raid into the Transvaal Boer Republic’s heartland to ‘liberate’ disenfranchised British citizens, the so-called Uitlanders, in booming Johannesburg. Lady Sarah described the event as, “No upheaval of Nature could have created greater amazement, combined with a good deal of admiration and some dismay.”

In the months leading to her brother Lord Randolph’s untimely death in January 1895, Lady Sarah had assumed control of his business affairs in southern Africa. This was a family development that fuelled the mutual hatred that existed between her and Lord Randolph’s elder son, Winston Churchill. In a clash of forceful and powerful personalities, Lady Sarah distrusted Winston, whom she held in low esteem, while Winston harboured extreme jealousy of her relationship with his father. To him she was a meddlesome mischief maker to whom he referred as “the cat”.

With the outbreak of the Second Boer War in September 1899 imminent, Lady Sarah accompanied her husband, Captain Gordon Wilson, to South Africa, but unlike the other officers’ wives who had made similar trips, she was adamant that she would not stagnate in Cape Town with the other socialites. That August Captain Wilson took the train north to Bulawayo to report for duty. Lady Sarah travelled with him. At Bulawayo she met Colonel Robert Baden-Powell who had been asked by the War Office to raise two mounted regiments to defend the Bechuanaland Protectorate (future Botswana) and the British South Africa Company-owned Rhodesia from Boer invasion. As chief scout to Imperial and locally raised forces during the 1896 Matabele Rebellion campaign, the future founder of the global Scout movement was deemed to have the right credentials to fulfil the brief. Baden-Powell, electing to base himself in Mafeking, took on Captain Wilson as his ADC.

Lady Sarah was required to remain in Bulawayo, but after a while she had enough of the ennui in Bulawayo, and caught a train south She alighted at Mafeking, ending her intended trip to the Cape.

Early in October, upon receiving word of an imminent Boer attack, Baden-Powell, who found Lady Sarah’s presence intolerable, ordered her to leave for Cape Town. However, excited at being so close to the opening shots of the war, she made a dash for Mosita, an African settlement 25 miles farther away from the border. From here she acted as a conduit for the dissemination of news about the Mafeking siege to the outside world. Carrier pigeons and a ‘trusty’ tribesman were used to clandestinely bring reports out of Mafeking. However, news spread of her activities, and early in December she was taken captive by the Boers on charges of espionage. She was held in Boer commander General Snyman’s laager, where he offered to swap Lady Sarah for a Boer horse thief languishing in a Mafeking jail. Baden-Powell rejected the offer, and an exacerbated Snyman threatened to send the troublesome English woman to the Boer seat of government in Pretoria where she could find a ‘pleasant ladies’ society’. The condescending sexist remark infuriated Lady Sarah, who stormed through the Boer headquarters and hospital, giving all in her way a barrage of insults.

With added pressure in Mafeking from Lord Edward Cecil, fourth son of Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, Baden-Powell relented, and Lady Sarah returned to Mafeking, after “two months of wanderings”, in exchange for Viljoen. Living in a bespoke underground bombproof bunker where she could entertain six for dinner, Lady Sarah dedicated much of her time to nursing the wounded and ill in the hospital. She readily adapted to a life filled with deprivation and constant danger from Boer shelling and attack. Her despatches for the Daily Mail were now more regular, informing the readership that, “The siege of Mafeking is no joke. Death is ever-present with us, a stern reality.” The siege was lifted with the arrival of a 2,000-strong flying column on 17 May 1900.

Lady Sarah Wilson died in London on 22 October 1929, aged 64. Not known as an outspoken advocate or champion of feminism or emancipation of the Victorian woman, she was fiercely independently minded. She made the most of her privileged situation in life to quench her insatiable thirst for personal adventure. She was not one of the exceptional female Victorian humanitarians who defied the male military establishment in South Africa, but for a married woman to enter a war zone entirely on her own went against everything deemed as proper for the time. She was way ahead of her time.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.