In October 1979, factional communist rival and Afghan Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hafizullah Amin, ordered the assassination of the Afghan president, communist Taraki Nur Mohamed, founder member of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) that had seized power a year earlier.

Amin assumed power, but Moscow labelled him “a power-hungry leader who is distinguished by brutality and treachery,” whose dealings with the Kremlin were insincere and duplicitous. For long reluctant to respond to Amin’s appeals for assistance, or to intervene directly, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and the Politburo, driven by growing concerns that the Soviet was going to lose control over a region of strategic interest, decided to act.

Following a phased, relatively limited deployment of troops and assets over several weeks, on December 27, 1979, Soviet airborne forces attacked the Presidential Palace in Kabul, during which Amin was killed. The Soviets replaced him with Karmal Babrak, and over the next two days the Soviet Fortieth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Yuri Tukharinov, invaded Afghanistan. The force comprised three motor rifle divisions (MRD) and the 103rd Airborne Division.

All the while, the counter-revolutionary Mujahideen, aided by Pakistan, Iran and the USA, continued to increase their armed activities against anyone or anything—especially the Amin regime—that represented a threat to their centuries-old socio-political existence centred on family, tribe and religion. Any semblance of national unity has historically been the consequence of outsiders trying to impose alien rule on the country, such as the nineteenth century British.

Although largely untrained, the hardy Mujahideen were thoroughly accustomed to the use of weapons in a part of the world where conflict resolution through the barrel of a gun was endemically ingrained in their lives.

The main weapons of the Mujahideen had to be compatible with the mobile tactics of guerrilla warfare. They were therefore equipped with the ubiquitous AK-47 assault rifle, PK light machine guns and the RPG-7 anti-tank rocket grenade launcher. The employment of 60mm, 82mm, and sometimes 107mm mortars, 82mm recoilless anti-tank guns, BM-1 single 107mm rocket launchers, and 7.62mm and 12.7mm heavy machine guns became more widespread. These tribal fighters were also enthusiastic proponents of landmine warfare, which the Soviets discovered at their expense, losing 1,191 vehicles and 1,995 men to mines.

Very little of Afghanistan’s terrain is suited to mechanised warfare, that relied on unhindered manoeuvrability and superior firepower, and in fact, provided the Mujahideen with an enormous strategic advantage. There were no railways and only 11,000 miles of roads, of which only one sixth was paved. The national Afghan Army was largely unable—or disinclined—to take on the warlords. This was the start of a ten-year occupation. Four years later, to the day, ABC World News presenter Peter Jennings reported with remarkable foresight:

“Four years after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, an unwinnable war drags on, unwinnable for either side. These are some of the Afghan guerrillas who prevented a Soviet victory, but they’ve not prevented Soviet domination.”

“There are slightly more than 100,000 Soviet troops in Afghanistan, which is about the size of Texas. U.S. intelligence estimates it costs the Soviets about $3 billion. Why, after four years, have the Soviets not done better? First they miscalculated because they couldn’t control the Communist regime that took over in 1978, and then they miscalculated in 1979 because they thought that they could be in for six months and stabilize things and leave. What superpowers often do, they forget that the mere presence of foreign soldiers in other countries becomes the main issue.”

By 1984, the American Central Intelligence Agency CIA) estimated that, since the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the Soviets had suffered roughly 25,000 casualties, including about 8,000 killed. They had lost over 600 helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft, and thousands of armoured vehicles and trucks. Casualties in the Afghan Army were around 67,000 and insurgent casualties at some 40,000. Analysts would describe the conflict as “the Soviet Union’s Vietnam War.”

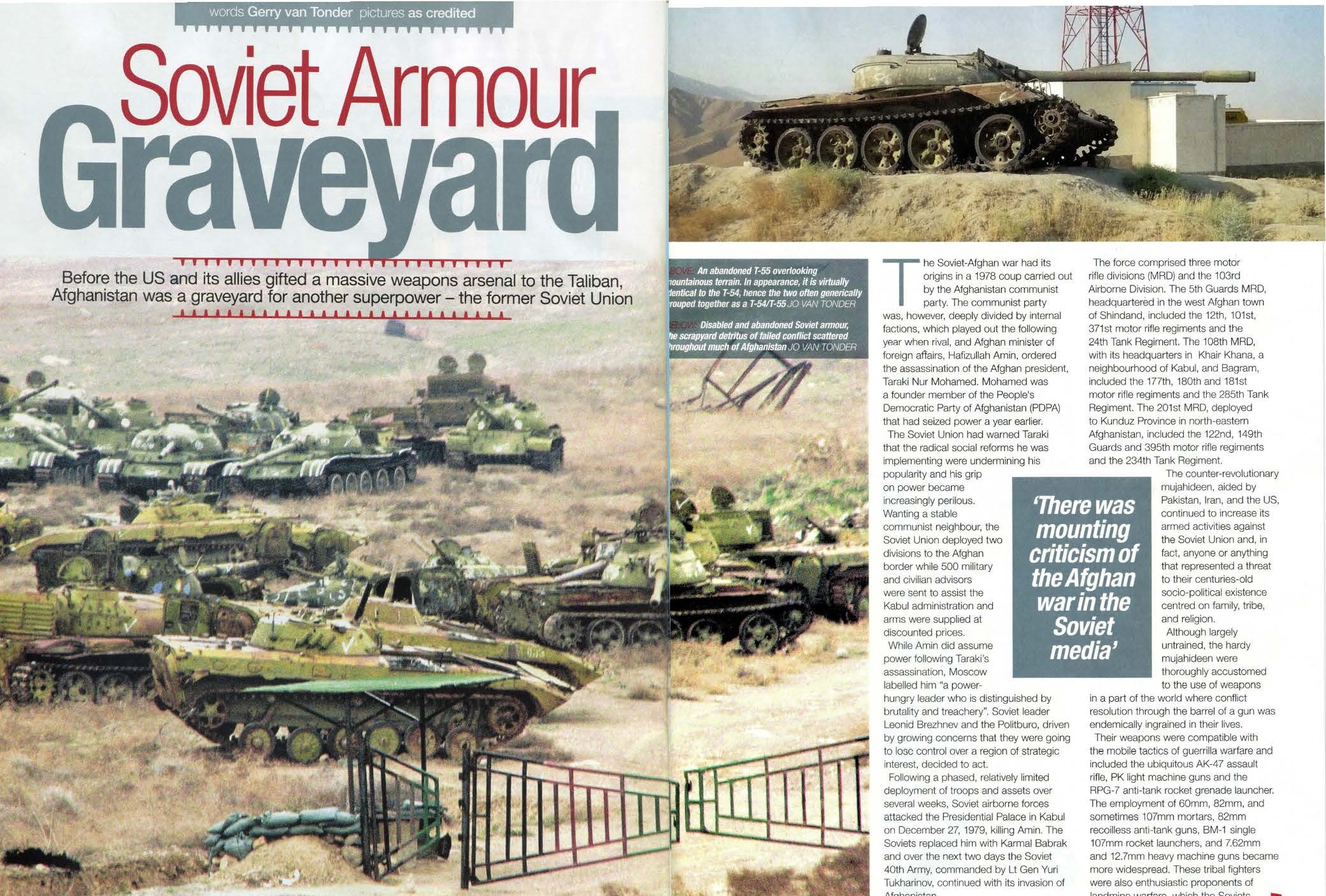

Between 1980–85, Soviet forces in Afghanistan lost 655 armoured vehicles and 340 tanks, and a staggering 5,250 tracks for armoured vehicles. Landmines, often stacked in threes, and remotely detonated explosive devices exacted a major toll on Soviet armour. According to the same 1987 CIA report mentioned above, the Soviets deployed an estimated 40 T-54/55 and 690 T-62 main battle tanks (MBTs).

By the late 1980s, there was mounting criticism of the Afghan war in the Soviet media and by the man in the street, likening the conflict to the disastrous Vietnam War. Early in 1987, the demobilisation of Soviet conscripts in Afghanistan commenced. This was followed by the Fortieth Army starting their official withdrawal in May 1988, and in February 1989, the last Soviet troops left.

On February 11, 1989, as the massive convoy of the Soviet Army Western Afghanistan Division trundled through the Afghan border town of Towraghondi and into the Soviet Union, armoured assault leader Lieutenant Viktor Yevdokimov said to accompanying British journalist Arthur Kent, “We could have tried anything, and the outcome would have been the same. It’s time to go home.”

And right now, 32 years later, Britain and the United States are also withdrawing their troops from that eclectic amalgam of fiercely zealous tribes and warlord polities that the rest of the world calls Afghanistan.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.