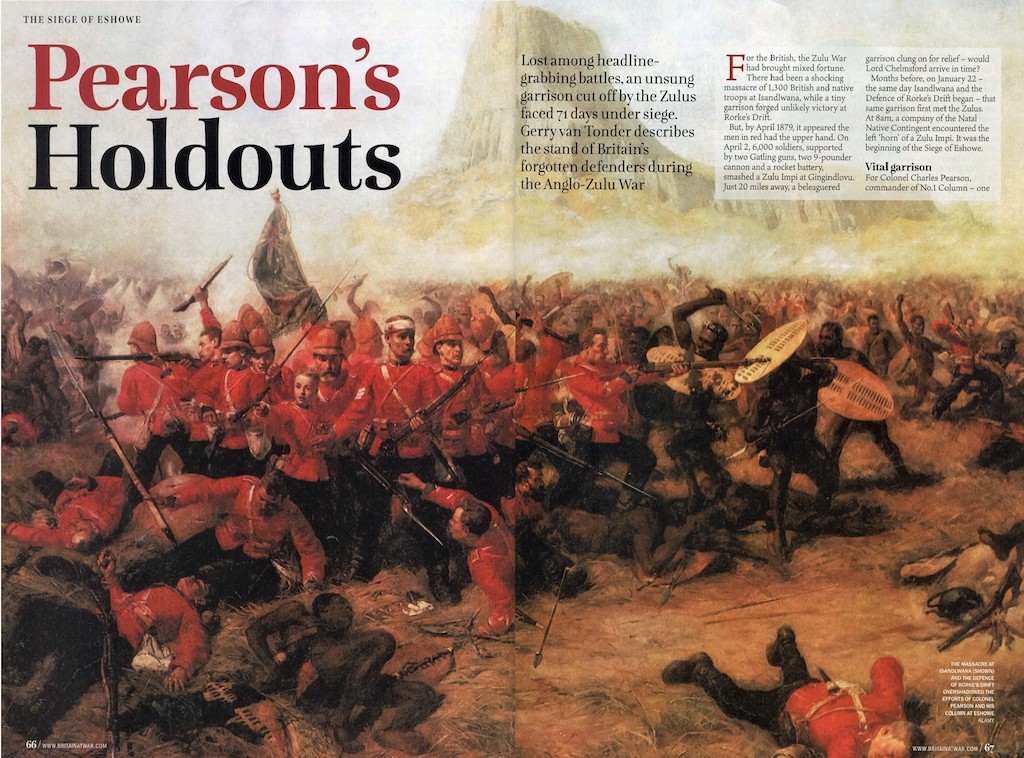

As commander of one of the three self-contained columns constituting Lord Chelmsford’s invasion force into Zululand in January 1879, Colonel Charles Pearson diligently studied his commander’s instructions. Notwithstanding the ominous and very real possibility of having “the whole Zulu force” descend on his Eshowe garrison, the quintessential Victorian army officer’s response was unequivocal. And, perhaps blissfully so, Pearson was totally unaware of the unspeakable disaster that, five days earlier, had befallen his brothers-in-arms some 100 miles to the northwest at a hill the Zulus called Isandlwana.

For Pearson, withdrawal was simply not an option. His original orders had been to establish a fortified garrison at the remote Eshowe mission station in Zulu king Cetshwayo’s territory. It would be from this position that Chelmsford intended to launch the final battle against the king’s seat of power at Ulundi.

Perceived criminal misdemeanours under British law by certain senior Zulu men would be the catalyst for Lord Chelmsford’s fateful, three-pronged invasion of Zululand on 12 January 1879. Chelmsford and his headquarters staff rode with the centre column, commanded by Crimean veteran Colonel Richard Glyn of the 24th Regiment, while Victoria Cross recipient, Colonel Evelyn Wood, 90th Regiment, led the left column. Colonel Charles Pearson, who had seen action at the siege and fall of Sebastopol, commanded the right column.

Establishing a forward camp on the Lower Tugela—Fort Pearson—to facilitate the river crossing and to provide a supply and logistics base, Pearson’s command was ferried across the river in a 30-foot pont hauled by oxen. Consolidating on the right bank, the column comprised over 400 men from six companies of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd ‘the Buffs’ Regiment; 160 from three companies of the 99th (Duke of Edinburgh’s Lanarkshire) Regiment; 138 Naval Brigade (Blue Jackets) men from HMS Active with two 7-pounders, one Gatling and a Hale rocket tube; 23 troops of the Royal Artillery with two 7-pounder muzzle-loading guns; 90 Royal Engineers; 115 locally raised mounted infantry; 117 Colonial troopers; 1,655 officers and men of the 2nd Regiment, Natal Native Contingent (NNC); and 60 of No. 2 Company, Natal Native Pioneers.

Numerous engagements with Zulu impis dogged Pearson’s column as he fought his way to Eshowe. On 23 January, the day after the Isandlwana tragedy and the gallant defence of Rorke’s Drift, the column reached the old Norwegian mission station at Eshowe. Pearson set about creating a well- defended depot for this line of Chelmsford’s invasion of the Zulu kingdom. A reliable source of water was close enough to be defended from the fort, and to save on food, he sent back the mounted men of the NNC to the Lower Tugela base, retaining 1,200 British troops for whom he had 320 rounds per man in store.

A week later a message arrived from Chelmsford,

Consider all my instructions as cancelled, and act in whatever manner you think most desirable in the interests of the force under your command. Should you consider the garrison of Eshowe as too far advanced to be fed with safety, you can withdraw it. Hold, however, if possible the posts on the Zulu side of the Lower Tugela. You must be prepared to have the whole Zulu force down upon you. Do away with tents, and let the men take shelter under the waggons, which will then be in a position for defence, and hold so many more supplies.

But Pearson refused to withdraw, even as food and ammunition reached dangerously low levels. During this time, Pearson went on the offensive, sending out attack patrols. Finally, after a major battle at Gingindlovu, late on the afternoon of 3 April Chelmsford led elements of the relief force into Eshowe. During the 10 weeks’ blockade, 4 officer and 27 other ranks had died.

Against all odds, Colonel Pearson had clung on to this isolated British military outpost, despite suggestions from Lord Chelmsford that he return to the Lower Tugela. Historians still ponder what the outcome may have been had Cetshwayo rescinded his orders not to attack British forts. Another Isandlwana? Rorke’s Drift? Regardless, the selfless actions of Pearson and the men of his column were brave and determined, and certainly beyond the call of duty.

Upon entering Eshowe Chelmsford immediately came to the conclusion that the fort would, after all, not be retained. The intricate defences Pearson had laboriously constructed were dismantled and the fort evacuated. Four days later the Zulus put Eshowe to the torch, and on 4 July, Cetshwayo’s capital at Ulundi fell to British forces.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.